Carving a Future for Puppetry: A Conversation with Oliver Hymans

Marking 35 Years of QEST — investing in the future of craft

For London-based puppet artist and theatre maker Oliver Hymans, receiving a Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST) Stanley Picker Scholarship in 2021 marked the beginning of an important new chapter — one that strengthened his practice and helped safeguard a centuries-old tradition.

“Being supported by QEST opened doors I never could have imagined,” Oliver reflects. “I had the privilege of studying with the last remaining marionette makers in the UK — a rare and extraordinary opportunity that shaped my craft and my perspective forever.”

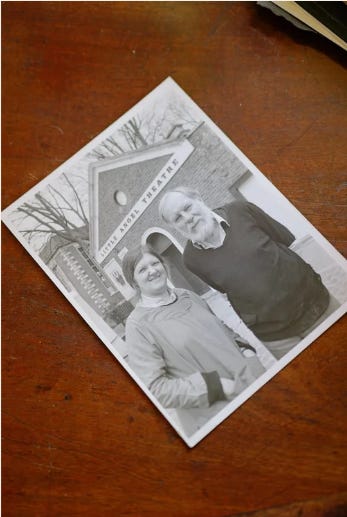

A graduate of Central Saint Martins and now Associate Director at the Little Angel Theatre, Oliver’s work bridges traditional craftsmanship and contemporary theatre. His puppets have appeared at Tate Modern, the V&A, and even Milan Design Week, where he recently took part in the Homo Faber Fellowship 2024, a prestigious European programme celebrating intergenerational craft exchange.

Learning from the Masters

Through his QEST scholarship, Oliver trained with two of Britain’s most respected puppet makers: Lyndie Wright, co-founder of Little Angel Theatre and a master carver whose puppets have graced film and stage for over six decades; and Stephen Mottram, known internationally for his exploration of marionette movement and the psychology of motion.

Q: For readers who may not know them, could you tell us a little about your teachers, Lyndie Wright and Stephen Mottram, and what you took from those experiences?

I spent five weeks with Stephen Mottram in Oxford, working in his beautiful studio surrounded by a lifetime of puppets and experimentation. Stephen is known internationally for his exploration of biological movement in marionettes—this idea that carved wood can appear to shift weight, breathe, hesitate, and behave in ways our subconscious reads as real. His puppets are extraordinary: they use sixteen strings (more than the 9 strings of a typical human figure here at Little Angel) and are engineered so they can transfer balance between their feet and even walk backwards, which is surprisingly rare in marionette practice.

What I really took from Stephen was not just the technical understanding of his mechanisms, but his belief in the psychology of motion. He spoke about the audible gasps he would hear from audiences when a puppet achieved something they didn’t think was possible—those moments when the illusion crosses into something uncanny and magical. Being immersed in his world and seeing the puppets he’s made throughout his career… It was hugely inspiring.

With Lyndie Wright, co-founder of Little Angel Theatre and an icon of British puppetry, I focused on finishing and bringing a marionette to life. I had begun carving the puppet in Devon with the wonderful John Roberts, of Puppet Craft UK (I highly recommend catching one of his summer courses), who has a long and influential history with LAT. In terms of finishing the puppet, Lyndie guided me in all aspects relating to the painting, sealing, protecting the wood, and all the subtle surface work that gives a puppet its character and longevity. It’s an entire craft of its own, separate from carving.

Lyndie’s workshop beside the theatre is full of history, and many of the puppets I’ve come across at LAT carry her distinctive design sensibility. She is a true custodian of the craft, and spending hours at her workbench felt like being plugged directly into the lineage of British marionette-making. It reinforced for me how important it is that these skills are passed on—without support and training, this craft could so easily slip away.

I also want to mention my time with Robert Randall, one of the country’s leading historic woodcarvers and former head of Historic Woodcarving at City & Guilds. I felt it was important to seek guidance from someone rooted in the tradition of fine carving, and Robert was an exacting, generous teacher. He taught me discipline in caring for my tools and even instilled a strict ban on sandpaper in the workshop—encouraging me instead to carve cleanly and precisely straight from the chisel.

Each of these teachers gave me something different: Stephen’s curiosity about movement, Lyndie’s mastery of finishing and design, John’s deep connection to the craft, and Robert’s precision and respect for the material. Together, they shaped not just my technical skills, but my sense of responsibility to carry marionette-making forward for the next generation.

Safeguarding an Endangered Craft

In 2022, Oliver collaborated with Heritage Crafts, the national charity for traditional skills, to have marionette making officially added to the Red List of Endangered Crafts — a register identifying heritage practices at risk of disappearing from the UK.

The listing was an important step in drawing attention to the fragility of the art form.

With further support from the Endangered Crafts Fund (backed by the Pilgrim Trust and the Radcliffe Trust), Oliver now runs specialist marionette-carving courses for professional makers at Little Angel Theatre in London.

Q: Where can people train in marionette making today? You’ve started running courses yourself, but are there other opportunities across the UK — and do you hope to see more teachers emerge in future?

A big part of receiving support from QEST and the Heritage Crafts ‘Endangered Crafts Fund’ was my commitment to give something back to the sector. It didn’t feel right to receive such specialist training without finding a way to pass it on to the wider puppetry community and to a whole new generation of makers. I come from a teaching background, so I’m very aware of the importance of showing people of all ages and backgrounds that craft can be a viable, impactful career — especially now, when traditional handmade skills are enjoying a real revival.

At Little Angel Theatre we have committed ourselves to running a marionette-carving course each term. In the 2+ years since we began, we’ve welcomed five cohorts — around twenty-five marionettes have been made so far — and it has been incredibly rewarding to see professional and hobbyist makers engaging with the craft at such depth.

Beyond LAT, the only other UK training in traditional carved marionettes that I’m aware of is run by John Roberts of Puppet Craft UK. John is not only a superb maker but a wonderful teacher, and his courses have been hugely influential for many of us. One of the reasons marionette making was added to the Red List in the first place in 2022 is that so many of the remaining master makers are at or nearing retirement. John has often said each year may be his last, yet he continues to run summer courses — which I fully understand; it’s hard to step away from something you love. His workshops range from three or four days to a full week, and they’re absolutely worth seeking out while they’re still available.

I absolutely hope more teachers will emerge. We’ve had some exceptional trainees come through the Little Angel Theatre recently, on our flagship Design Traineeship, and I’m confident that several of them will become marionette-making tutors in their own right. The more people passing on the craft, the more resilient its future will be.

For anyone interested in the courses at Little Angel Theatre, I’d recommend joining our mailing list — they tend to sell out within hours of being announced!

Q: If someone reading this wanted to learn, or perhaps host a workshop, what would you suggest as a first step?

From a practical point of view, if you’re looking to start carving or run a session yourself, the first step is investing in good tools. Marionette making can become expensive at the outset, but if you buy well and look after your tools properly, they’ll last a lifetime. The puppets themselves are not costly to produce — we mostly work with sustainable materials such as linden (lime) wood — but the craftsmanship behind them relies on having the right kit.

There are also techniques within marionette making that have been passed down from generation to generation and are still held by a small number of masters. So if you’re completely new, I’d really recommend signing up for at least one course to build good foundations. And if cost is a barrier, there are excellent funding options available, particularly through Heritage Crafts, which specifically supports people looking to train in endangered skills or purchase equipment.

Of course, there’s plenty in books and also online — YouTube can be a great starting point for understanding the basics — but nothing compares to getting a chisel in your hand and making those first cuts into a block of wood.

The Homo Faber Fellowship

Oliver’s work received further recognition in 2024, when he was selected by the Michelangelo Foundation for the Homo Faber Fellowship — one of Europe’s leading craft initiatives. The programme pairs experienced artisans with emerging makers to share skills, create new work, and ensure that traditional techniques are passed on to future generations.

Q: For those unfamiliar with the Homo Faber Fellowship, could you tell us more about what it is and what it involves?

Absolutely — it was an extraordinary opportunity, and I have to thank QEST for encouraging us to apply. Coming from over fifteen years of puppet-making within the theatre and performing arts sector, I was relatively new to the wider “craft” world, and I hadn’t realised how significant Homo Faber is. As puppetry gains more recognition within the craft sector, it feels like a very exciting moment for makers like myself.

Homo Faber is a major international movement for contemporary craftsmanship, supported by the Michelangelo Foundation. Its mission is to celebrate, preserve, and promote high-level handmade skills for future generations — whether through its global online artisan directory, the Homo Faber Guide, or its biennial exhibitions in Venice, which bring together artisans, patrons, collectors, and cultural institutions. It’s really about ensuring that craftsmanship remains a viable, valued profession.

For the Fellowship, I applied with Ash Appadu, who had recently completed his design traineeship with me and the design department at Little Angel Theatre. The programme centres on a seven-month skills handover between a master artisan and an emerging maker. It begins with a month-long residency in Venice for the trainees, delivered by the International University of Art in Venice (UIA Venezia) and includes masterclasses with partners such as ESSEC Business School and Passa Ao Futuro. Their training focuses not only on practical craft skills but also on the entrepreneurial side of sustaining a career in fine craftsmanship – something I would have loved to have received at the start of my career!

All the Master Artisans, including myself, then joined Ash and their respective fellows for the final weekend of the Venice residency, which coincided with the Homo Faber Biennale – a huge exhibition of craft that takes place on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, within the historic buildings of the Fondazione Giorgio Cini — a former Benedictine monastery with extraordinary architecture and views across the lagoon. Experiencing the exhibition together was incredibly inspiring. Our work as puppet makers is usually made for the knocks and bumps of a live theatre stage, so seeing craftsmanship displayed with such reverence and beauty was a completely different perspective on what puppetry can be.

The second phase of the Homo Faber Fellowship continued with a six-month paid internship for Ash in my studio, culminating in the co-creation of two marionettes for Milan Design Week. These pieces were exhibited alongside the work of 22 other master artisans and their trainees from across the world. It was a huge privilege — and surreal — to see our marionettes presented in an international design context, and more than 20,000 people visited the exhibition over the week.

Q: What did you gain from that exchange, both as a maker and as a mentor?

The Fellowship was invaluable for both of us. As a maker, it gave me the chance to share my practice with the next generation while also pushing myself to try new techniques and refine areas of my own craft. As a mentor, it was incredibly rewarding to watch Ash deepen his understanding of marionette-making — to the point where I’d now be completely confident in him producing his own show-ready marionettes.

We also gained the wonderful opportunity to exhibit our work at a world-leading international show in Milan. And the momentum from Homo Faber didn’t stop there: we were both invited to be headline demonstrators at London Craft Week, presenting our making process and puppets at the V&A Museum in May 2025. I was later invited to present my marionettes in Riyadh at the third annual Banan Festival — Saudi Arabia’s International Handicraft Week — in November 2025.

Perhaps most excitingly, the two puppets we co-created for the Homo Faber Fellowship — The Boy from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and The Broom — will be exhibited next year at the British Library as part of a landmark exhibition on fairy tales. For both of us, it’s been a transformative experience that has opened doors, strengthened our individual practices, and shown what can happen when traditional craft and contemporary puppetry are given space on the world stage.

Crafting Connection

Alongside his artistic practice, Oliver is also a Mental Health First Aider and a passionate advocate for the social value of puppetry. His work explores how puppets can foster empathy, imagination, and human connection.

Q: How do you see puppetry supporting wellbeing and mental health?

For me, puppetry is fundamentally about human stories — creating moments of empathy, reflection, and connection. A puppet can often say or show things that feel harder to express in “straight” theatre. Whether it’s creating a set of talking musical instrument puppets for a show tackling grief within families (The Instrumentals; Little Angel Theatre, Goblin Theatre, Blouse & Skirt Co-Production) or designing a show that explored anxiety and depression in childhood (Prince Charming, Little Angel Theatre) – there really isn’t a topic you can’t explore within the artform. There’s a gentle distance created by using inanimate objects, which paradoxically allows audiences to engage more openly with difficult themes, emotions, or memories. That can be incredibly powerful for wellbeing.

At Little Angel Theatre we see, every day, how puppetry fuels imagination and unlocks a sense of playfulness in people of all ages. And that impact isn’t limited to those who can come to our venue. Through our recent suitcase shows, we take puppetry into spaces where audiences may have little or no access to the arts — prisons, care homes, hospital wards, refugee and asylum centres. In those environments, puppetry can offer comfort, distraction, shared joy, or simply a moment of being transported somewhere else. It’s work we’re deeply proud of, and it’s a big part of why LAT was named The Stage’s Fringe Theatre of the Year in 2024.

As a Mental Health First Aider, I’m particularly aware of how creativity and storytelling contribute to emotional resilience. Puppetry invites us to project, imagine, and connect — and in doing so, it supports wellbeing in ways that are both subtle and profound.

Q: Have you seen examples of puppetry being used successfully in education or community work — and what makes it such a powerful tool for empathy?

Yes — and one project in particular has stayed with me for years. When I was freelancing early in my career, I worked with Turtle Key Arts, an organisation based in West London, that creates theatre with and for adults on the autistic spectrum. The participants had each spent several weeks designing and making their own alter-ego puppet, and I joined the project to help them bring those characters to life.

It was incredibly inspiring to see how confidently and creatively they expressed themselves through the puppets. Many of the participants found verbal communication challenging, yet when they worked through the puppet — their own creation, with its own personality and voice — something opened up. They communicated more freely and connected with others in ways that felt both safe and joyful.

That’s the power of puppetry in education and community work: the puppet becomes a bridge. It offers just enough distance to make vulnerability feel manageable, while still allowing people to express something deeply human. When we see a puppet move, we instinctively project emotion onto it — and that act of projection and recognition is at the heart of empathy. It’s why puppetry can be such a transformative tool for people of all ages and backgrounds.

Reaching Wider Audiences

As Associate Director at Little Angel Theatre, Oliver is part of a team creating productions that reach far beyond the theatre’s Islington home. Little Angel now streams performances internationally and collaborates with leading UK venues.

Q: Little Angel Theatre is known worldwide. How important is that platform for keeping puppetry visible and vibrant?

I’ve often heard people say that Little Angel Theatre “punches above its weight,” and I completely agree. Despite being a relatively small organisation, we have a truly global reputation. So many world-class puppetry artists have passed through our doors at some point — as performers, makers, audience members, or simply curious visitors who’ve heard about LAT and want to experience it for themselves. That legacy and visibility are incredibly important for keeping the art form alive and evolving.

Like many organisations, we stopped touring internationally after Covid. And, of course, Brexit has made it even more complicated to travel overseas both financially and logistically. But we’re now beginning to revisit that ambition, with some of our shows heading to Turkey and the Middle East in the next year. It feels exciting to be reconnecting with audiences beyond the UK again.

We’ve also been producing more mid-scale work over the past 3-4 years, which often begins life in our larger Studio 1 space before travelling to major venues around the country — and in some cases ending up in the West End over Christmas. Recent examples include Charlie Cook’s Favourite Book and A Squash and a Squeeze. And we’re now deep into design work for our next big show, Toto the Ninja Cat by Dermot O’Leary — which is particularly exciting for me, as it’s my first time designing at this scale.

Having a platform like LAT means we can champion puppetry on multiple levels: from nurturing emerging makers to producing work that reaches tens of thousands of families each year. That visibility helps keep puppetry vibrant, relevant, and firmly part of the cultural landscape — not just in the UK, but internationally.

Q: For those who might only have seen puppets on television or in children’s shows, what would you recommend as a first experience of live puppetry — for adults, children, and families?

Honestly, any of our shows at Little Angel Theatre are a brilliant place to start. We programme work for all ages — from beautifully gentle pieces for babies and early years, right through to ambitious storytelling and visually rich productions for older children and their families. I also programme our summer Children’s Puppet Festival in August each year (next year will be our fourth iteration) and I always try and book something for everyone, whether it be puppet shows with comedy, opera, mime or classic story telling.

Supporting the Future of Puppetry

Although puppetry is one of the world’s oldest art forms, in the UK it often struggles to find a clear home within national funding structures.

At present, puppetry tends to fall under broader categories such as theatre or circus within Arts Council England, which can make it difficult for puppeteers — whether makers, performers or designers — to have their work recognised as a distinct discipline and receive funding.

Q: Puppetry isn’t always clearly defined within funding frameworks like Arts Council England, often being grouped under theatre or circus. How does this affect makers and performers, and what can audiences or the wider arts community do to help change that?

At Little Angel Theatre, we regularly feel the effects of it. We’re competing for the same funding pots as much larger children’s theatre organisations, yet puppetry is our specialism, and at present it isn’t recognised as a distinct discipline within Arts Council England or other major funders. That lack of definition makes it harder for puppetry practitioners — whether makers, performers, designers, or companies — to make the case for why our work needs specific investment and support.

One of the challenges is that the puppetry sector is quite dispersed: many brilliant companies, organisations and guilds, makers and solo artists are doing their own work in their own corners of the industry. What we really need is a stronger collective voice. If the sector can rally together and advocate for puppetry to be recognised in its own right, we can then begin to address the issues that are unique to our field: the physical demands and injuries associated with puppeteering; the need for contracts that properly protect puppet makers’ intellectual property; specialised training routes; and funding structures that acknowledge the craft heritage, technical complexity and labour involved.

Without puppetry having its own category, I genuinely believe it holds the sector back from accessing the level of support required to push the art form forward.

As for what audiences and the wider arts community can do: engage, advocate, and amplify. See puppetry, talk about it, champion the companies and makers whose work you value. Public appetite and visible demand make a huge difference when funders are shaping priorities. And when audiences and industry peers join the call for puppetry to be properly recognised — not as a subcategory, but as a standalone art form and craft — it strengthens the case for long-term change.

Q: How important is it that puppetry is recognised as its own art form — so that those who make and perform with puppets are credited just as actors, designers and craftspeople are?

It’s absolutely vital. We experienced this very recently with a puppet commission for a pretty major client, where our team, initially, wasn’t properly credited or recognised for the craft expertise involved. I don’t believe there was any ill intent — the client probably hadn’t worked with puppets in this way before and assumed our work was similar to general set building or prop-making. But that misunderstanding is telling, and it’s damaging. It diminishes not only our craft, but also the highly skilled companies they work with across all areas of production.

At Little Angel Theatre, we’re fortunate: we have a long-standing reputation, deep experience, and the confidence to advocate for ourselves. But many independent makers — especially emerging artists who may not have formal representation — are far more vulnerable. If puppetry isn’t formally recognised as its own art form, it becomes easier for the labour, artistry and intellectual property of puppet makers and puppeteers to be overlooked or undervalued.

Proper crediting isn’t just about ego; it’s about professional visibility, fair pay, and safeguarding the future of the craft. And I hope that continued recognition from organisations such as QEST, Heritage Crafts, and British UNIMA will help strengthen puppetry’s visibility within the cultural sector and encourage wider investment. Their support already signals to the industry that puppetry is a serious, sophisticated discipline — and the more that message spreads, the better protected future makers and performers will be.

Q: For audiences who love puppetry but may not wish to make or perform, how can they support the craft and the people keeping it alive?

The simplest — and most important — thing you can do is keep coming to live theatre. Truly, your presence as an audience member makes all the difference, especially at a time when people are feeling the financial squeeze and the cost of creating work has risen dramatically. Every ticket purchased helps sustain the artists, makers, performers and venues who keep puppetry thriving.

Another meaningful way to support the craft is to consider becoming a member of Heritage Crafts or other similar organisations that support puppetry like British UNIMA. With Heritage Crafts, your membership directly contributes to safeguarding endangered skills, funding trainee bursaries, and providing practical support to craftspeople across the UK. And as a member, you also have a voice in how the organisation is run, which means you’re actively shaping the future of traditional crafts — puppetry included.

Q: Do you think more collaboration between theatre, design, and craft sectors could help elevate puppetry’s profile and funding potential?

Absolutely — and I’ve touched on this already — but collaboration and collective action are essential if puppetry is going to secure the recognition and support it needs. One of the most important developments on the horizon is the UK’s recent ratification of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage framework, or what Heritage Crafts and DCMS (Department of Culture Media and Sports) are calling Living Heritage.

This framework protects practices that are intangible — skills, techniques, performance traditions, culinary arts, spoken heritage — rather than physical monuments or buildings. In other words, it’s about safeguarding cultural knowledge that is traditionally passed from person to person, generation to generation. Puppetry, and marionette-making in particular, fits perfectly within that definition.

DCMS will soon be creating the UK’s first Living Heritage inventory, and it is absolutely vital that we nominate marionettes and rally support across the sector. Recognition at that level would help us move beyond funding solely for the making of puppets and towards sustainable funding for the performance of puppetry — which is, after all, the whole point of the craft. At the moment, puppetry sits between the arts and crafts sectors, and although both value it, neither has historically been willing to fund the full lifecycle of the work, from making to staging.

This is where collaboration becomes crucial. If theatre organisations, designers, craft bodies, and puppet-makers come together with a shared voice, we stand a much better chance of elevating the profile of marionette puppetry specifically, improving funding structures, and protecting the skills that keep the art form alive.

We’re already putting plans in motion at Little Angel Theatre to support this effort.

Why Puppets Matter

Q: Why do you think puppets continue to captivate people, even in a digital age?

There’s no doubt that puppetry has had a real resurgence over the past 15 years. War Horse was a turning point — not just for me personally, but for the whole theatre sector. It showed directors and audiences alike what puppetry could achieve emotionally and theatrically. Since then, we’ve seen the huge success of productions like Life of Pi and My Neighbour Totoro, which have firmly established puppetry as part of mainstream commercial theatre.

And it’s not just on stage. In film and television, there’s been a noticeable return to practical effects — creatures, characters and environments made by real human hands instead of solely relying on CGI. I think audiences are starting to crave that authenticity again. They can feel the difference between something handcrafted and something digitally generated; there’s a tactility to puppets that makes you believe you could reach out and touch them.

I grew up in the 1980s with films like Star Wars, Gremlins and Labyrinth, all full of extraordinary puppet and creature work. Those worlds felt real precisely because they were real — built, stitched, sculpted and performed by teams of designers and puppeteers.

And then there’s AI. It’s undoubtedly going to reshape many industries, but for now I think puppet makers are safe. AI has its place — I often find it useful at the very early stages of a project for idea generation — but people are increasingly valuing things that are handmade and infused with the human touch. Puppets offer something that digital tools can’t replicate: a direct, empathetic connection to an object that comes alive through human skill.

Ultimately, puppets captivate us because they sit in that magical space between the real and the imagined. They’re tangible, beautifully crafted objects — and yet, the moment they start to move, we invest them with life. In an age saturated with screens and digital imagery, that kind of imaginative, physical storytelling feels more precious than ever.

Q: What can a puppet express that perhaps a human performer cannot?

For me, it’s not that a puppet can express emotions that a human performer can’t — both have the potential to carry the emotional heart of a story. The difference lies in what a puppet allows you to do theatrically. A puppet can move through worlds that a human body can’t inhabit; it can be magical, fantastical, symbolic or utterly otherworldly. It can transform, float, shrink, break apart, or defy gravity, all while remaining deeply connected to the emotional narrative.

Puppets also create a unique imaginative space for an audience. Because they are objects brought to life, viewers project their own feelings onto them. A tiny tilt of the head or a stillness in the body can speak volumes — sometimes more subtly or poignantly than an actor could. That blend of simplicity and possibility is what makes puppetry so transportive.

So it’s less about limitation and more about expanded potential. Puppets can take us places that humans simply can’t, while still allowing us to feel something profoundly human in the process.

Q: And finally — why do you believe puppetry is worth saving?

Well, I wouldn’t be here at all if the craft hadn’t captured my imagination long ago.

But more than that, I’m beginning to realise that my calling is to be a custodian of it — to hold it up, to shine a light on it throughout my life and career, and to help ensure there are many others ready to carry the flame long after I’m gone.

Puppetry is one of the world’s oldest art forms, yet it remains endlessly inventive, imaginative, and capable of touching people in ways few other mediums can. To let it fade would mean losing not just a craft, but a way of storytelling, of connecting, of understanding ourselves and one another.

That’s why it’s worth saving — and why I’ll spend my lifetime fighting for it.

Looking Ahead

Oliver continues to carve, teach, and collaborate — developing new work that blends heritage craftsmanship with contemporary storytelling. His goal remains simple but profound: to keep the craft alive by using it.

Q: What’s next for you, and what would you most like to see for the future of marionette making in the UK?

There’s a lot to be excited about — it’s definitely not all doom and gloom. At Little Angel Theatre, we’re determined to get marionette making off the Red List of Endangered Crafts. It’s ambitious, but ambition is exactly what the moment calls for.

We’re about to apply for significant funding to bring the historic marionette bridges at LAT back into action. But this isn’t just about putting on a few shows and congratulating ourselves – we know funders want to see more than this. The real goal is growth — building a proper training pipeline that creates a whole new generation of marionette makers and performers, alongside increasing the engagement with the public, raising awareness of the cause. If successful with the bid, there’s a whole series of public-facing events and activities which is also very exciting.

We’ve also secured support to expand our puppet making workshop into something bigger, better, and far more public-facing. More details will be announced soon — watch this space.

Personally, I feel like I’ve spent the last five years flying the flag for marionettes, always standing on the shoulders of the giants who came before me. Now it’s time to do the thing that matters most: make a show. Because in the end, marionettes belong on stage — and that’s exactly where I want to put them.

Website: www.oliverjameshymans.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/buddyollie

About the Organisations Mentioned

QEST (Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust) — Founded in 1990 by the Royal Warrant Holders Association, QEST supports excellence in British craftsmanship. Over 35 years, it has funded more than 700 scholars across 130 different disciplines.

www.qest.org.uk

Heritage Crafts — The national charity for traditional heritage crafts and a UNESCO-accredited NGO for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Heritage Crafts works to protect endangered skills across the UK and provides small grants through its Endangered Crafts Fund.

www.heritagecrafts.org.uk

The Michelangelo Foundation’s Homo Faber Fellowship — An international programme pairing master artisans with emerging makers to promote the transmission of traditional skills across Europe.

www.homofaber.com

Little Angel Theatre — Based in Islington, London, Little Angel is the UK’s leading puppet theatre. It presents original productions, touring work, and education projects, and streams performances worldwide.

www.littleangeltheatre.com